Historical Review of Champaign’s City Buildings Over The Years

by Dannel McCollum

Former Champaign Mayor (1987-1991)

The First City Building…

After the Village of West Urbana was incorporated, the first regular meeting of the Village Board was held on April 28, 1857, at the “Brick School House.” While much of the record is missing, and what survives, more often than not, is not specific, it would seem that board meetings for perhaps the first year and longer continued to be held at the Brick School House. The structure, built in 1855, was the first public school in West Urbana and stood on the lot located at the southwest corner of Hill and Randolph Streets.

Then, on May 12, 1858, after the meeting location had not been noted for a number of weeks, the record specified that, on this occasion, the meeting was held in “lW. Baddeley’s store.” Baddeley was the first postmaster in West Urbana and was elected to the first Village Board in 1857.

There is no indication in the sketchy record that the Board ever returned to the school house. Instead, over the following decade, board meetings were held in the offices of either various board members, the city attorney, or the police magistrate. In the meantime, on February 21, 1861, West Urbana received full legal sanction from the State Legislature to function as the City of Champaign.

After a little longer than a decade of meeting in private or semi-private locations, the Council decided upon a more formal setting for its deliberations. Sometime between the spring and fall of 1869, the Council leased “Council Rooms” from RM. Eppstein. Rent was $16.67 per month.

The rental arrangement sufficed for nearly a decade. Then, at the Council meeting of January 17, 1888, Alderman lB. Weeks “urged the necessity of the erection of a City Building.” By motion, the matter was referred to the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds “to procure plans for same.” By August 21, plans had proceeded to the extent that the Council had received at least six site proposals, including one from Ald. H.H. Harris. The locations were: corner of Main and Walnut; corner of Walnut and Taylor; corner of Main and Chestnut (the Harris site); corner of Market and University; the Doty Building on Oak Street; the present site of the City Building.The last site was the only one offered free of cost to the City. Harris did not vote for his site, and at some point during the deliberations, he withdrew it from consideration.

In a poll, the two latter sites enjoyed clear, though not majority, support. A meeting was held on the following day to resolve the site issue. A letter was received from Edward Bailey, Esq., clarifying David Bailey’s (his father) offer to donate a site, “provided the City would erect thereon a City Building not costing less than $5,000, to be erected within five years … ” After informal balloting, the Council formally voted 7-0 to accept the Bailey site. Other decisions made at the meeting included an appropriation of $100 for visits by members of the Buildings and Grounds Committee to examine other City Buildings, a cost limit on the new building of $15,000, and by a very close vote, that “a suitable room be provided in the new City Building for the use of the Public Library.”

During the month of September 1888, the topic of the new City Building was constantly before the Council. A number of architects submitted letters expressing interest. In dealing with the various proposals, it was decided that the cost of the building should not exceed $12,000, down $3,000 from the amount previously decided upon. Of the four sets of plans submitted, only one came from a local architect, Seeley Brown of Champaign, who was selected.

Architect Brown had a significant task before him. He was charged with designing a building which would, in addition to the library, have to include all city operations -the Council Rooms, the Engine House (previously a separate facility), and a police station/jail. The latter would replace the “Calaboose” (a city-owned stone structure standing on land rented from the “Railroad Co.”).

While the cost of the proposed building seems miniscule by today’s standards, it still represented an amount far beyond what the City had in its treasury. The Finance Committee was given the task of “devising ways and means to replenish the depleted City Treasury.” In late January 1889, acting upon the recommendation of its committee, the Council had prepared $20,000 in bonds to cover building costs and other obligations. The bonds were issued in four increments of $5,000 each through November of 1889. Expenses of the issue were reported as follows: printing: $20, telegraphing: $ 2, Total $22.

Edward Bailey, Esq., son of the donor of the land, was the purchaser of the bonds when bids from bankers in other cities proved to be unsatisfactory. Bids for the new City Building were opened February 19, 1889. Three of the four bids were less than $100 below the $12,000 limit; the fourth was $365 over. None of the bids included plumbing and heating. J. Dickerson of Champaign, the low bidder by $16, was awarded the contract.

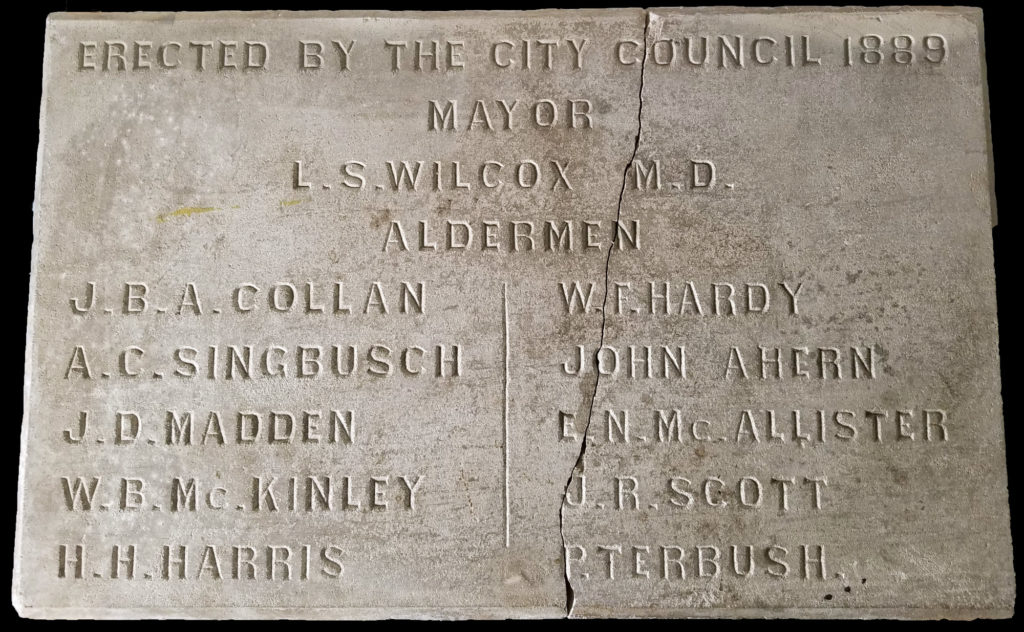

By April 1889, work on the building was in progress. Given the low conditions in the downtown area, it was found necessary to spend an additional $29 “to raise the grade of the new building.” The cornerstone was another matter of urgency, since much of the building was to rest on top of it. There was some disagreement as to the stone’s location -the southwest or the northwest comer of the building; the Council decided upon the latter placement. The inscription stated the following:

Building Erected 1889

Mayor: L.S. Wilcox

Aldermen: J.B.A Collan, A.C. Singbusch, J.D. Madden, W.B. McKinley, H.H. Harris, W.F. Hardy, John Ahern, E.N. McAllister, J.R. Scott, P. Terbush

Apparently there was a ceremony on the occasion, for Ald. J.B.A Collan “was instructed to procure carriages for the Council with appropriate decorations.”

At the meeting of June 4, 1889, Ald. J.R. Scott “suggested that the Building Committee should have the prison in the new building prepared for use as soon as possible, as the present one (the Calaboose) is unfit for its purposes.” Some two months later, the Council accepted the bid of Champion Iron Works for “cages for the city prison.”

Later in August, Ald. Harris “informed the Council that the drain leading from the City Building was not low enough to carry off the water from the building and that it should be lowered at least 18 inches down to the creek.” One is left to wonder just what fluids the ten-inch drain was to carry, although there were “water closets” in the building serviced by a cistern. The nearest creek was the Boneyard, which has carried away whatever was piped into it over the years.

As the new City Building began to take shape, the Council considered such details as the sidewalk in front of the building. Ald. Joseph O’Brien suggested that a stone walk eight feet wide and four inches thick of Cleveland Stone be laid in front of the building. While it is not clear just what sort of sidewalk was actually laid, a stone walk similar to that described survives at the northwest corner of Market and Taylor Streets.

By September, the building was nearing completion. Ald. Harris raised the question of furnishing the building. Quincy Show Case Works was selected as the supplier. Included in the $1,050 bid was $600 for furnishing the library – the latter amount not charged to the cost of the building. Another extra was $70 “for graining woodwork.”

At the meeting of November 19, 1889, Ald. John Ahern reported that a party was interested in “renting the old engine house when it was vacated.” Also, the lease on the Calaboose lot had expired. As the Railroad Co. did not wish to renew the lease, the Building Committee was “instructed to remove the building and dispose of same.” Evidently, the prison in the new building was already in use.

The first meeting of the Council in the first City Building was held on December 3, 1889. At that meeting, the Building and Grounds Committee delivered a final account of the costs; the total cost was $15,073.78, of which $11,623.00 went to the general contractor. The Building Committee took considerable pride in the final result as the last two paragraphs of its report indicate:

“In looking over the work as it progressed, your Committee can see few mistakes to correct or errors to regret. All material used in construction and fixtures were the best of their kind; all labor was honestly performed, and will stand any just inspection or criticism. The foundation had to stand the severest test by being flooded several times through the severe rainstorms of last season, yet no crack or flaw appears in any part of the building. In turning this building over to your honorable body, and through you to the citizens of Champaign, your Committee feels free to assert that for the amount of money invested in the building and its fixtures throughout, it stands second to none, and is a monument of which the citizens of this city may well feel proud.”

“The long-felt want of a suitable building for the city offices, public library, and fire department has at last been supplied. Each department now complete in itself, separate and distinct, under one and the same roof; each department commodious and easy of access, with sufficient capacity to meet the requirements of this city for years to come. And now, in conclusion, may your Committee suggest that very soon the building be thrown open for general inspection by the citizens, that they may see for what their money has been used … “

Press coverage of the meeting in the Champaign County Gazette seemed to reflect general satisfaction with the new building:

“The council chamber in the new city building was dedicated last Tuesday night in an informal manner. The council held its first meeting therein, and there were a large number of spectators who were so interested in the proceedings that they lingered until the adjournment. The large and elegant room was lighted brilliantly, and the rich furniture showed off to excellent advantage. The Aldermen lounged lazily in their tiling armchairs, which they enjoyed so much that they seemed unwilling to adjourn.”

On January 7, 1890, the Building Committee reported that “all the fire apparatus has been moved into the new building … ” As far as the Committee could judge, “the Fire Department of Champaign is now complete, and will compare favorably with any in Illinois outside of Chicago … ” (Pride in its Fire Department is not new in Champaign!)

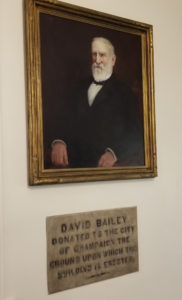

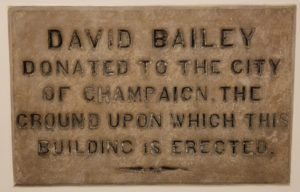

In an effort to maximize the public benefit, the Council voted to permit the Champaign Boards of Education (there were two districts at the time) and the Board of Directors of the Champaign Fair Association (the fairgrounds were located just east of First Street, south of Green) to use the City Engineer’s room “for the purpose of holding their meetings.” The following August, the Council belatedly recognized the generosity of David Bailey by having a stone inscribed recognizing his donation of the land. (This stone has been built into the foyer of the present City Building.)

In 1896, the Burnham Athenaeum building was opened to the public, allowing the library to move into its first “permanent” home. The library room presumably was assigned to other city uses.

The Second City Building…

The original City Building did not age well. By 1935, after only 45 years of service, the floor had settled in the fire house, and the structure appeared generally run down. Fire Chief John Ely, in a letter to Mayor James D. Flynn, wrote: ” … we have realized that it would take a considerable expenditure of money to build (new) quarters and care for the fire equipment as it should be cared for, but since President Roosevelt has seen fit to grant monies to cities and towns for the purpose of erecting public buildings, we urge upon you this necessity … ”

At the same time, there was also strong support to expand Burnham City Hospital. Both projects qualified under guidelines set for the distribution of Federal funds by the Public Works Administration (PWA). The Burnham project would consist of a new building adjacent to the existing hospital. The proposed new city hall would occupy the same site as the existing structure and house the same functions – City offices as well as the Police and Fire Departments.

On September 17, the Council called a special election for a $91,000 bond issue to pay for the majority portion of the proposed $175,000 structure. The remaining $84,000 was anticipated from the Federal PWA. The Council also called for a bond issue for the hospital. All of this was somewhat difficult for Mayor Flynn and his Council who had all, according to the News-Gazette, “stood on a platform … not to vote bond issues upon the people.” Accordingly, Mayor Flynn and his colleagues “remained silent” during the subsequent campaign, “preferring to let the voters decide the issue.”

Five days before the vote, the News-Gazette printed a decidedly favorable editorial on the issue. It argued that a new building had been needed for more than a decade. Equally, in apparent acceptance of President Franklin Roosevelt’s pump priming strategy, the writer argued that the project would put much-needed money into the local economy to the advantage of labor and business alike. The piece concluded: “Too long have we put up with a building that is a disgrace to a community of this size and type.” Local labor groups, unlike the mayor, did not remain silent. lW. Dunn, business representative of the Building Trades Council, was expansive in his support: “Can anyone who calls himself civic-minded and (can) be proud to say, “I am a citizen of Champaign,” look at the present, dilapidated old worn out City Building without blushing with shame?” The Twin City Federation of Labor joined in with its support as well.

Ambitiously, the Council scheduled the Burnham and City Building Bond referenda, back to back, on the 28th and 29th of October, respectively. On the day before the City Building vote, the News-Gazette, which supported both bond issues, gave the latter one last plug with a series of rhetorical questions on Page One:

“Will the voters approve the issuance of $91,000 in bonds to pay for a $175,000 City Building, the $84,000 balance of which is expected to be provided by the Federal Government as an outright gift?” “Is the City to keep abreast of the modern times with a new City Building, or is it to continue its government in a 47-year old building which long ago has served its usefulness?” “Above all, is Champaign willing to provide employment for numerous craftsmen and laborers in order that the community may prosper?”

By overwhelming majorities, four to one, the voters supported both bond issues. Mayor Flynn broke his silence, saying: “I’m going to do everything in my power to get a new City Building for Champaign; no stone will be left unturned.”

The Council proceeded with deliberation on the City Building project. Within a month, following voter approval, Mayor Flynn was authorized to advertise for bids for “the construction of a City Building, PWA Project, Illinois No. 1315.” At a special meeting in December, the Council awarded the construction contracts. The low bidder for the general contract was the Wm. Kuhne Company of Rantoul. The structure was initially envisioned as a “monolithic concrete building” with lesser cost options of either brick or stone facing. Ultimately, the Council chose a brick facing with Bedford stone rim.

Since the existing building was to be razed to make way for the new, the Council had to provide temporary space for City operations. City offices and the Police Department shifted to the Walter Stern building located at 322-324 North Hickory Street. (Later, that building became the nucleus of the Sears and Roebuck Store in Champaign.) The Fire Department remained behind, but prepared to move “on a moment’s notice” to 202 E. University Avenue.

It has been said over the years that the architect, George Ramey of Champaign, used as the inspiration for his design the Los Angeles City Hall, built a decade earlier. According to a 1988 brochure on that building, “the (Los Angeles) city fathers decided that they must build a building which would set an example for governmental buildings all over the world.”

The Ramey design did incorporate the art deco tower so prominent in the Los Angeles structure. Hardly could the Los Angeles city fathers have known when their structure was built that the art deco style would flower so monumentally during the decade of the 1930s as the Federal Government sought, among its many strategies, to spend its way out of the Great Depression.

William Kuhne, in announcing plans on New Year’s Day for the prompt demolition, added: “We intend to salvage and sell as much as possible in order to pay the cost for wrecking the old building.” Times sure have changed in that respect: labor costs would prohibit such a procedure now. Today it would be the wrecking ball and a quick trip to the landfill. Kuhne estimated that demolition could be accomplished in 30 days.

The Fire Department’s move to its temporary quarters came on January 2, 1936. Its carefully coordinated move was detailed in the News-Gazette. The firemen moved their beds first; they then returned for their lockers and other equipment. “The last thing we will move will be the trucks,” said Assistant Chief Roy Alsip. “Then we’ll send the first alarm trucks over with a crew, then notify the telephone company to cut the phones over to the other place. Finally we will take the other three pieces of equipment – the aerial and the second alarm trucks.”

The day after the Fire Department moved, Mayor Flynn, Contractor Kuhne, and Police Sergeant James Cochrane, in an “informal” inauguration of the project, “tugged at and tore off (the) handrail into Police Magistrate George James’ former Police Court … ” But Kuhne’s 30-day demolition scheduled encountered early difficulties. The subcontractor experienced a work stoppage over a wage dispute. Within three days, the PWA administrator ruled that “unless union men are furnished within 48 hours, Kuhne will be free to employ anyone he wishes … ” Then a period of severe weather intervened. For nearly a month, no major work occurred. Finally, in early February, crews began removing the roof of the old building. During the process, the “stop-and-go light” at Neil Street and University Avenue wore a “protective frame hat.”

Also, in January, the City Council confirmed the sale of $91,000 in City Building bonds and shortly thereafter levied a tax to repay the same. Construction proceeded apace. The early intent for a partial basement was changed to a full excavation. During this phase, the contractor encountered “quicksand” which, along with cave ins, occasioned by heavy rains and vibrations from the traction cars, slowed as well as added to the cost of the project. By August 1936, it became necessary to hold a second election to approve an additional $25,000 “for the purpose of defraying the cost of completing the construction of and equipping a City Building.” In October, the Otis Company bid for the tower elevator was accepted.

Well into the cold weather of late fall 1936, the building passed the point of 50 percent completion, and required heating. This was provided by steam heat produced by the Illinois Power and Light Corporation. It supplied heat to most downtown buildings through spent steam from its electrical generating station on North Neil Street.

In December, the Council granted the first of a series of extensions to the contractors. Relatedly, the Council directed the City Clerk to extend the lease on the temporary city building on a month-to-month basis.

The main Council construction concern during January of the new year was the new jail. It was to be located in the basement of the new building.

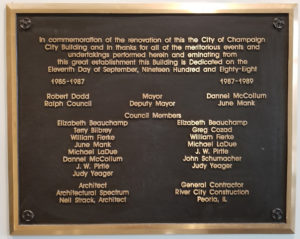

By April, after more time extensions to the contractors, the project had reached a point at which the Council felt it to be appropriate to consider the two plaques it intended to place in the foyer of the new building. The award for the plaques went to the S.P. Atkinson Co., not the low bidder but located conveniently in the next block south on Neil Street. At the same time, the Council deemed it necessary to spend nearly $11,000 to repave the area around the new building.

In May, the still unfinished building was closed enough to completion for the City and the general contractor to agree upon its partial use by the Fire Department. Finally, on July 13, 1937, the Council formally accepted the finished building from the contractors.

The cumulative result of the delays was a cost overrun. To help compensate, the City had successfully petitioned the PWA for release of funds, originally slated for furnishing the new building, for use in the construction phase. Foreseeing the problem this could create at the end of the project, the City Council asked the PWA for an additional grant to buy furniture and other furnishings. No word on the request was forthcoming from the PWA for months upon months. The result was, in July 1937, that the building was complete but unoccupiable.

This created a serious problem for the City Council. If it could not move City operations to the new building, it would be forced to continue to occupy its temporary quarters and pay rent. The News-Gazette painted the situation bleakly:

“Approximately enough of the old furniture is left to furnish one or two offices in the new building. That (furniture) is old, has been damaged by moving and use in temporary quarters. Without further funds, the City is faced with paying further (rent), being forced into the street, or furnishing the new municipal building with soap boxes and empty cartons.”

As the furniture dispute continued, a unique approach was undertaken to take care of the firemen who were already in the new building. A number of public-spirited citizens, acting independently, began a collection which furnished the first floor lounge as well as the offices of the chief and the assistant chief.

Near the end of August, matters reached a point where the City Council had to do something with or without the participation of the PWA. Contractor Kuhne was in the unenviable position of having completed his contract but being unable to collect his final ten percent of the contract, $19,000, until the PWA had approved all work on the project.

The City Council, unable to persuade the PWA, made two decisions; it ordered the new furniture it needed, and it set the date to move into the new City Building with what furniture and furnishings it had. The latter would serve until the new arrived from the suppliers. A bid of $95 was approved to fund the move. Finally, after nearly a month, City offices, as well as the Police Department, moved into and occupied the building. By mid-October, the new furniture had arrived, and the Council made plans for an open house.

The big event occurred during the first weekend in December, with the various city departments participating. The Street Department brought in some of its heavy equipment. The Police Department had two display boards, one featured confiscated weapons, the other, weapons used by the police. The Fire Department had its engines on hand. One objective of the open house was to demonstrate the poor state of the fire equipment so that the citizens would support still another bond issue to replace much of it. Less than a week later, on December 9, the strategy worked by a comfortable seven to one margin.

During the two-day open house, 1268 citizens registered as visitors. Unofficially, the count was placed at over 1500. After so many delays it was almost anticlimactic. Nevertheless, it was a beautiful and sturdy building, one that would prove worthy to stand the test of time.

Mayor Flynn, in his bid for re-election in 1939, offered an accounting of the total expenditures for the City Building. Of the total cost of $206,421, $116,000 was funded by bond issue, $12,967 came from the premium on those bonds, and $77,454 was furnished by WPA grant. The public must have been pleased, for the Mayor was re-elected.

The City Building has changed over the years. One of those changes occurred in 1960 when, during the first term of Mayor Emerson Dexter, the Council moved the formal council chamber from the relatively small tower quarters on the fifth floor to the second floor auditorium. The overall effect of the move must certainly have been to make the public feel more welcome at Council deliberations. Subsequently, during the term of Major Virgil Wikoff, the new chamber was extensively remodeled.

Visually, and functionally, a much more significant event occurred when, on May 28, 1967, the Champaign Fire Department moved out of the first and second floors of the east wing to the new central fire station located at 207 W. White Street. The News-Gazette described the event as follows:

“It turned out there were just enough men to drive all the trucks. At 10: 15 p.m., the thunder of the powerful engines reverberated from the black and white tiled walls for the last time.

“Elderly Pumper No.1, with Battalion Chief Ed Schalk at the wheel and Chief Ashby beside him, pulled out onto University Avenue. No.1 was followed closely by a big, modern pumper, and another middle-aged one. Then came venerable Aerial Ladder Truck No.4, which was new when the City Building fire station was new in 1937. The impromptu parade roared swiftly down University Avenue to State Street; then turned left down State to White Street and the new station.”

The resulting vacant space in the City Building was remodeled for use by the Police Department which, by then, had totally outgrown its location on the first floor of the tower and the basement. Unfortunately, the brick used to close off the bays formerly used by the fire trucks did not match that of the building.

On June 20, 1983, the police vacated the City Building, as well, for their facility at the corner of University Avenue and First Street. Chief of Police Donald Hanna remembered the event well – it was his first day on the job. This move left virtually the entire east wing vacant except for the second floor council chamber. The only outward evidence that the Police Department had even been there are the initials “CPD” (modified from “CFD”) in stone over the southeast door to the east wing.

The city administration had grown over the years, as had the other departments. Colonization of the vacated space by the remaining city departments now became a priority. The City Council never considered abandoning the City Building for another location. As the Council had done for both the Public Works Facility and the Police Station, it accumulated Federal Revenue Sharing monies to fund the renovation project. Serious work began when Architect Neil Strack was retained to direct the task. He was a fine choice, since the preservation of the distinctive character of the City Building, a Strack specialty, was an articulated priority of the Council.

There was not universal acceptance of the design which Strack submitted to the Council. Among other things, the basement was to be refitted for use as an “Emergency Operations Center” (EOC), for which Federal funding was available. Major opposition was raised by some Council Members who argued that this would necessitate the construction of a third floor over the east wing to make up for the space lost, adding greatly to the overall cost of the project. After a prolonged fight over the issue, the Council majority, led by Mayor Robert Dodd, opted for the EOC and the third floor addition.

In early 1986, partial demolition was authorized inside the vacant east wing. Work progressed to the point that, in September 1986, the Council was forced to vacate its chamber and to move its weekly meetings to the auditorium of the Public Library, where it would meet for the next 16 months. By fall 1986, the east wing was completely gutted; only the exterior walls remained. Then, as that portion of the structure took shape, some departments in the tower were moved out to various locations in downtown, while others moved from one floor to another as the renovation progressed. The Mayor’s and City Manager’s offices remained unscathed on the fifth floor until near the completion of the project, although the approaching noise of the jackhammers was unnerving in the extreme to those at the top.

On January 5, 1988, Council meetings resumed at City Hall. With the move of the executive offices from the fifth floor to the second floor in January 1988, only the Legal Department and the Building Safety Division offices remained outside. The Legal Department was slated for the fifth and sixth floors. The architect argued early in the project that the Mayor’s and City Manager’s offices should be moved to the second floor to be “closer to the people.” In effect, the executives traded spaces with the lawyers. A Council member commented at the time that the Legal Department was appropriately moved to the top floors “to be in the clouds.”

The Legal Department moved back in early March and the Building Safety Division office completed the homecoming on March 11, 1988. All contract work was completed and accepted in August. On September 11, 1988, the renovated City Building was formally rededicated.

Total renovation costs for the City Building amounted to $4,037,660. Of this amount, $2,456,700 came from Federal Revenue Sharing, $278,200 from a Federal grant for the EOC, and the remainder from City sources.